A Multi-Sensory Appendage

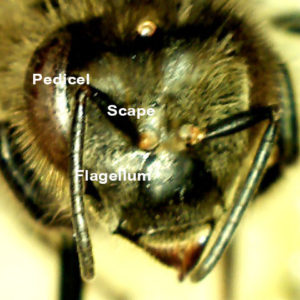

The honey bee antenna, delicate as it is, provides a wealth of information essential for function and survival of both the bee and the colony. It comprises the scape, which attaches to the honey bee head, the pedicel at the turn, and the long flagellum with its many subsegments. Its thousands of sensors relay information that include more than one sense—for example, some are involved in touch as well as smell.

The honey bee antenna, delicate as it is, provides a wealth of information essential for function and survival of both the bee and the colony. It comprises the scape, which attaches to the honey bee head, the pedicel at the turn, and the long flagellum with its many subsegments. Its thousands of sensors relay information that include more than one sense—for example, some are involved in touch as well as smell.

The antenna also provides the means by which the bee is able to sense vibrations carried from the movements of a dancing bee inside the beehive, i.e., can perceive sound. Yet, it was not all that long ago that we began to understand not only the means by which honey bees are able to detect such movements but also that they are able to detect them at all. As Snodgrass writes in his carefully drawn 1910 technical bulletin,

“In the case of the bee some authors have ascribed even a third sense, that of hearing, to the antennae, but there is little evidence that bees possess the power of hearing.”

The “power of hearing” would remain undetected until the 1990s.

An Organ of Cells Sensitive to Vibration

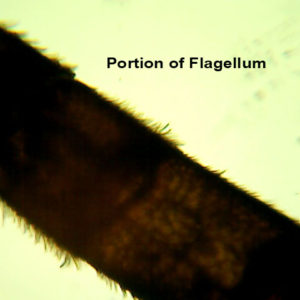

Although the bee has mechanoreceptors on the antennae, hairlike projections that respond to the movement of air, what we don’t see when we watch a forager move from blossom to blossom as she gathers nectar and pollen for her colony or as she senses the dance movements of another forager inside the beehive is the internal structure of the antenna. Therein lies the Johnston’s organ, one housed in the pedicel of each of the bee’s two antennae. This organ consists of a collection of around 300 cells that are sensitive to vibration. The primary avenue for hearing, the Johnston’s organ provides a means for detecting movement of the segment next to the pedicel, the antenna’s flagellum. Ever so slight and aided by its length, the flagellum is substantial enough to be moved by vibrations from nearby sources.

Although the bee has mechanoreceptors on the antennae, hairlike projections that respond to the movement of air, what we don’t see when we watch a forager move from blossom to blossom as she gathers nectar and pollen for her colony or as she senses the dance movements of another forager inside the beehive is the internal structure of the antenna. Therein lies the Johnston’s organ, one housed in the pedicel of each of the bee’s two antennae. This organ consists of a collection of around 300 cells that are sensitive to vibration. The primary avenue for hearing, the Johnston’s organ provides a means for detecting movement of the segment next to the pedicel, the antenna’s flagellum. Ever so slight and aided by its length, the flagellum is substantial enough to be moved by vibrations from nearby sources.

An antennal nerve traverses the length of the antenna, and axons from the Johnston’s organ reach into several areas of the honey bee brain. Mechanical impulses from the flagellum’s movement thereby translate into nerve impulses that then are transmitted to the mechanosensory portion of the brain—that then are interpreted by the bee.

A Brain with Many Connections

In fine-tuning our understanding of how the bee manages all this, researchers from Germany and Japan compared certain neurons known to be sensitive to vibration in a newly emerged worker with those of a foraging honey bee. These are the DL-Int-1, neurons thought to function in helping the bee encode the duration of the waggle phase of the bee dance, the portion of the dance that indicates distance of the resource from the beehive. They are interneurons, association neurons, and serve to transmit impulses between neurons. They help complete the circuit.

Adult honey bee workers become more adept at perceiving the waggle movement as they age, i.e., as they become foragers. And, as it turns out, both the morphology and the response of the DL-Int-1 change with age. The research notes that the connections within the network are refined and that the processing of the waggle dance signals taking place in the brain is improved; branches get trimmed up, and information is handled more efficiently. Whether these changes are part of a natural development process or instead result from the bee’s foraging activity, or otherwise, remains unknown.

We’ve learned much about the additional sensory capacity of the honey bee antenna—its “power of hearing,” that indeed gives power to the bee, and its additional capacities to inform the bee of taste as well as such environmental conditions as temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide—since Snodgrass noted that “it must be realized that only intelligent guessing is possible where several senses [touch and smell] are located on the same part.” Although tremendous steps have been taken along the way, we clearly have a wonder-full ways to go!

Ajayrama Kumaraswamy, Hiroyuki Ai, Kazuki Kai, Hidetoshi Ikeno and Thomas Wachtler. Adaptations during Maturation in an Identified Honeybee Interneuron Responsive to Waggle Dance Vibration Signals. eNeuro 26 August 2019, 6 (5) ENEURO.0454-18.2019; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0454-18.2019.

R.E. Snodgrass. The Anatomy of the Honey Bee. 1910. Technical Series No. 18. US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Entomology.